Sleep architecture measures after one single oral morning... | Download Table

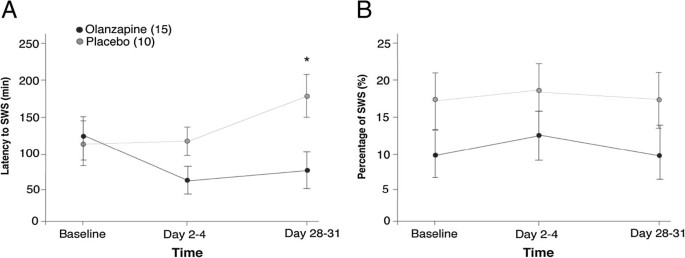

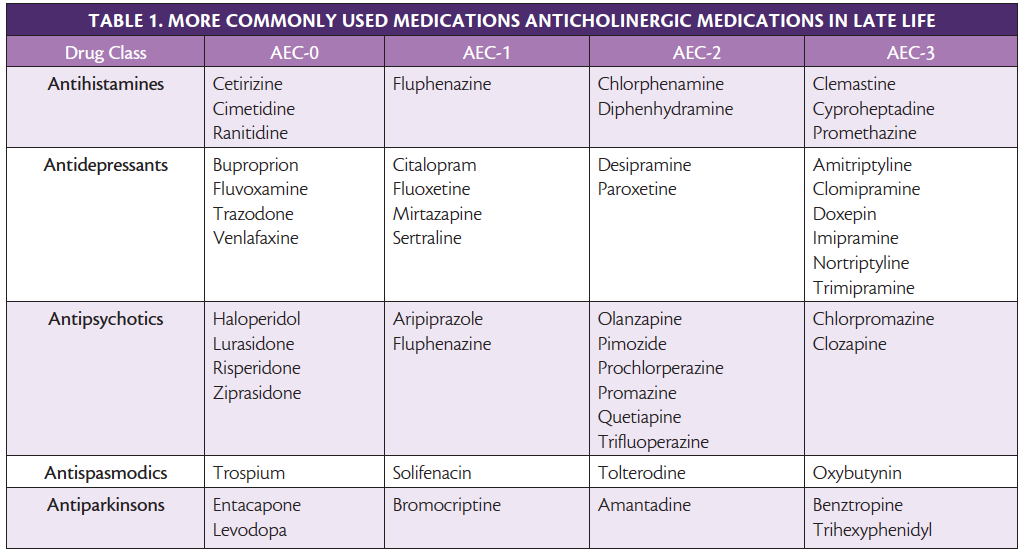

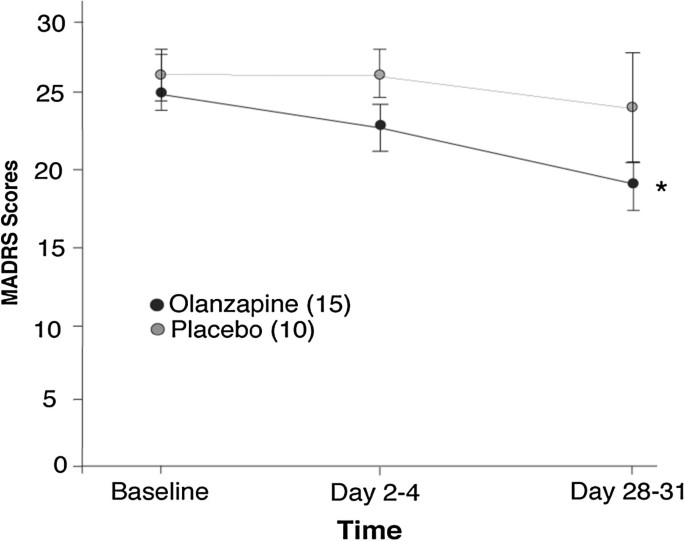

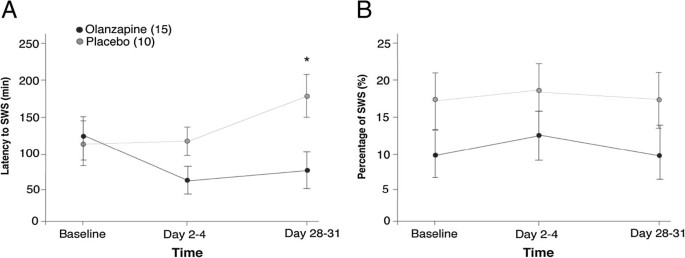

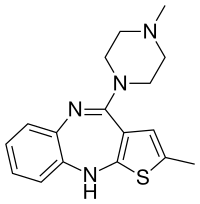

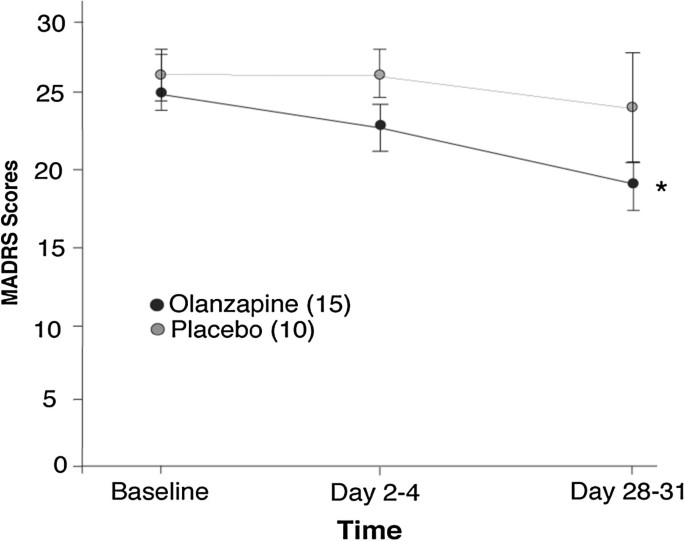

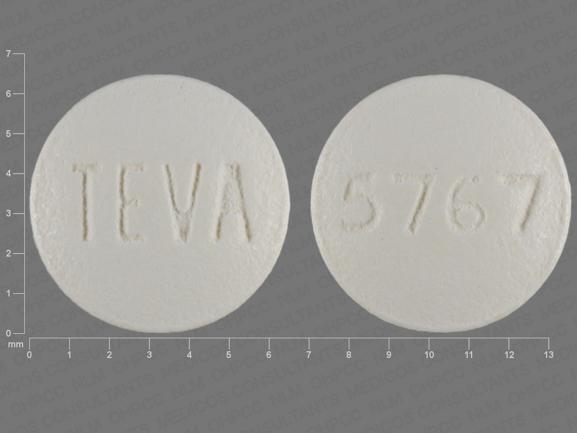

Sleep architecture measures after one single oral morning... | Download TableAdvert Dream Architecture and Cognitive Changes in Patients Treated with Olanzapine Depression: A Placebo-controlled double-blind trial volume 14, article number: 202 (2014) Volume 1410k Accesses17 Citations2 AltmetricAbstractBackgroundDisturbance in sleep quality is a symptom of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and Bipolar Disorder (BD) and thus improving quality of sleep is an important aspect successful of treatment. Here, a prospective, double-blind, randomized, and placebo-controlled study examined the effect of olanzapine wave enhancement therapy (an atypical antipsychotic) on dream architecture, specifically slow sleep (SWS), in the treatment of depression. The effects of olanzapine enhancement therapy on other sleep characteristics (e.g., sleep continuity) and depression (e.g., severity of disease and cognitive function) were also identified. MethodsPatients who experience an important depressive episode and who were in a stable medication were included. The dream architecture was measured by outpatient polysomnography during the night. The severity of the disease was determined using the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Classification Scale (MADRS). The cognitive function was examined by the Cambridge Automated Neuropsychological Test Battery (CANTAB): Space Work Memory (SWM), Span Space (SSP), and Reaction Time Tasks (RTI). Polysomnographs, clinical measures and cognitive tests were given on the basis, after 2-4 days of treatment and after 28 to 31 days of treatment. Twenty-five patients participated in the study (N = 10, N = 15 for treated groups of placebo and olanzapine respectively). ResultsThe main objective of the study was to evaluate the objective (polysomnographic) changes in sleep quality, defined as changes in SWS, after the olanzapine treatment for depression. Latency to but not duration of SWS was found to significantly differ between olanzapine- and placebo-treated participants (Hedge's g: 0.97, 0.13 respectively). A significant improvement was observed in participants treated with olanzapine on participants treated with placebo in secondary performance measures, such as sleep efficiency, total sleep time and late sleep. Side objectives evaluated subjective changes in sleep quality parameters and related them to disease severity measures and cognitive changes. MADRS scores significantly improved in participants treated with olanzapine over time, but no more than placebo treatment. There was no significant difference between participants treated with olanzapine and placebo in SWM, SSP or RTI tasks. Conclusions The treatment of increase of the olapine generally did not improve the SWS, but improved the continuity of sleep and depression. Olanzapine may be one of the few drugs that improve sleep continuity, pointing directly to symptoms of depression. Court RegistrationClinicalTrials.gov, . Background Sleep quality disorder is a symptom of major depressive disorder (MDD) and bipolar disorder (BD) [], with MDD having the strongest association with sleep disorders [, ]. It is well documented that the severity of sleep disturbance is related to the response to treatment, as well as chronic disorders [, ], and as such, is an important aspect of treatment. The dream has two main components: Rapid Eye Movement (R) and Non-REM (N) sleep []. Sleep N includes stages 1 to 3, where stage 3 is called slow wave sleep (SWS). SWS is considered the deepest stage of sleep and implies a higher excitation threshold []. This is the most common stage of the sleep cycle in the first third of the night, approximately 10%-15% of total sleep time (TST). As the SWS shortens in each cycle, the amount of R sleep increases, with the most prevalent R sleep during each cycle in the final third of the night, accounting for 20%-25% of TST []. Sleep architecture in patients who experience depression is usually thought to be altered []. Sleep during depressive episodes is characterized by a reduction in SWS, or increased latency to SWS, longer sleep duration R, lower latency to sleep R, continuity disorders and decrease TST [–]. The altered SWS and R sleep are seen in approximately 50% of patients with affective disorders []. Sharpley et al. [] found a negative association between SWS activity and the severity of depression disease; however, variables such as sleep efficiency and TST were also found with a significant increase as the severity of the disease decreased. Cognitive deficits in MDD and BD include work memory, care and psychomotor speed [–]. It has been shown that acute and chronic sleep deprivation affects attention, work memory and cognitive function [–]. In healthy volunteers, SWS deprivation was associated with poor cognitive performance and delayed reaction time when awakening [, ]. In particular, studies have shown that the duration of SWS per night is correlated with the performance of work memory in older and schizophrenic samples [, ]. However, the role of sleep in cognitive performance in patients with mood disorders is unknown. Monoaminergic neurotransmitters are believed to be involved in the relationship between sleep and depression. Serotonergic systems [, ], cholinergic [], histaminergic [, ], and noradrenergic [] contribute to the physiopathology of depression and underlying mechanisms of sleep. Antidepressants may cause changes in the sleep electroencephalogram (EEG) of depressed patients, the most prominent being sleep suppression R. This is thought to occur by increasing the norepinephrine (NA) and/or serotonin function (5-HT) []. 5-HT receptors have also shown a critical role in SWS regulation. Several antidepressants, in particular tricyclic and trazodone antidepressants, are believed to standardize SWS due to their affinity for 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors []. It has been estimated that up to 30% of patients with depression do not respond to traditional antidepressant treatments only []. The increase in antidepressant therapy, with olanzapine, antipsychotic atypical, is often used in routine clinical practice for the treatment of depression. Olanzapine has affinity for dopamine D1, D3, and D4; serotonin 5-HT2A/C, 5-HT3 and 5-HT-6; muscarinic M1-M5; adrenergic α1; and H1. In addition, olanzapine is an antagonist in these sites, with greater affinity for dopamine and serotonin receptors []. To date, many studies have focused on improving the severity of illnesses in patients with multiple transmission disorder or stress disorder by combining humor stabilizer drugs with a change in sleep-related behaviors [–]. A review by Riemann et al. [] described several different interventions used to improve sleep habits of patients with MDD, such as psychotherapy [], pharmacological treatment [], and sleep deprivation therapy [], among others. A large majority of these studies, regardless of the type of treatment, found that improving sleep continuity measures led to improvements in mood. Olanzapine has shown to increase sleep continuity, subjective sleep measures and SWS in healthy volunteers [–], while an association between changes in sleep architecture and mood improvement in patients with MDD remains unclear []. Finally, it has been shown that Olanzapine improves cognition in schizophrenic patients []; however, its impact on cognition in depressive patients has not yet been fully described. The main objective of this study was to examine the effects of the treatment of increased olanzapine in the dream architecture, specifically SWS, in patients who experience an important depressive episode. In addition, we examine several secondary measurements of results to determine the effects of olanzapine agumentation on other elements of sleep, such as TST and sleep continuity, and aspects of depression, including the severity of the disease and cognitive function. MethodsThe present study was a prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled, repeated, polysomnographic study. This study was approved by the research ethics board of the University of the Queen, Health Canada, and was registered with clinictrials.gov (NCT00520507). Participants A change of 15% to the main result measure, SWS, was selected to be a clinically significant and significant change; this effect size was used to calculate the sample size, indicating that 30 participants (15 placebo, 15 treatment) were necessary to have enough power to detect an olanzepine effect in SWS. To account for the abandonment, we intend to register 40 participants. However, the way was stopped before reaching the recruitment targets (May 2009) owing to the inability to hire participants. Only thirty-one participants signed informed consent to participate in this study. Participants were examined and enrolled in the study (as of October 2007) by blind doctors ( nurses) and recruited by units of mood disorders of tertiary care, general practitioners ' offices and the community. They were all 18 years old or older, and met the DSM-IV-TR [] criteria for MDD, Bipolar I Disorder, Bipolar II Disorder or Disorder Bipolar NOS, as confirmed by the Mini Inventory Neuropsychiatric International (MINI) []. In registration, participants experienced an important depressive episode (MDE), defined as a Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-17 item (HDRS-17) score of √15, and not a mixed episode, defined as a Young Mania Rating Scale Score (YMRS) of ≤ 12 []. The excluded criteria were the current or past diagnosis of schizophrenia or dementia, substance abuse within three months of enrollment (excluding caffeine or nicotine), imminent risk of suicide or danger to themselves or others, intolerance known to olanzapine, severe or insufficiently treated medical disease, a history of seizures, prior registration in the study or registration in another study within four weeks of treatment. Participants cannot take any other antipsychotic medication at the time of registration and should have been taking a stable dose of all medications for 4 weeks before enrollment. 2 , 2 , 2 , 2 , 2 , 1 , 2 , 1 , 2 , 1 , 2 , 1 , 2 , 2 , 1 , 2 , 1 , 1 , , 1 , , 1 , , , , , , 1 , , , 4 participants failed in the baseline projection (1 had a HAMD) Thus, 25 participants were included in the analysis. Three participants of the group treated with olanzapine finished the study before the day 28–31, due to a worsening of the original mood symptoms. Participants were monitored for apnea and/or hypopnea throughout the course of the study as the presence of these conditions at any time justified the exclusion of the study due to the confusing nature of these events in the dream architecture. Participants are not required to be removed due to obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea. Clinical measures The participants were evaluated in three time points by a physician blinded to the treatment group: base (before randomization and administration of study medications), 2-4 days and 28 to 31 days after the administration of study medications. Each clinical evaluation consisted of the HDRS-17 [], the Montgomery Asberg Depression Scale (MADRS) [], the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HARS) [, ], the YMRS [], the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [], Visual Analysis Scale (VAS) for sleep quality [iness], and the Epworth Sleep In the reference line, the MINI and the Global Clinical Printing (CGI-S) [], the scales were administered. On 28–31, the Global Clinical Impression (CGI-I) was administered. Blood tests, physical exams and pregnancy tests (in women with child-raising potential) were performed. Neurocognitive Measures In each visit, participants completed cognitive tests using three tasks of Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB), including: Span Span Space (SSP), Spatial Working Memory (SWM) and Reaction Time (RTI) [, ] (Cambridge Cognition, Cambridge, UK; ). A participant did not complete the CANTAB tests. Medication Participants were randomly assigned to placebo or olanzapine conditions (oral disintegration, zydis, formulation). A randomization table was generated by a statistician to randomize for the order that then placed sealed envelopes containing a single assignment (A:Placebo, B:Olanzapine) in a box in the order specified by the randomization table. After the projection, the participant was ordered to remove the following envelope in the box. This assignment was given to a non-blind pharmacist who filled a prescription saying "placebo/olanzapine". Drug dosage began at 2.5 mg on day 1 and increased to 5 mg per day 2; during day 2-4, dosage was lured up or down, in increments of 2.5 mg to a maximum of 20 mg. The average dose of olanzapine was 6.67 mg at the end of the study; the doses ranged from 5 mg to 10 mg. Eight participants in the treated group with placebo and twelve in the treated group with olanzapine were taking at least one antidepressant as concomitating drugs; antidepressants including amitriptyline, bupropion, escitalopram, citalopram, doxepin, venlafaxine, fluoxetin, remeron and trazodone. A participant in the treated group with placebo was taking only a benzodiazepine; a participant in the group treated with wave zapine was taking only one mood stabilizer; one participant in the treated group with placebo and two in the group treated with olanzapine were not taking any other psychotropic medication. All concomitant drugs were stable over the duration of the study. Polysomnographic recordings At every time, a night sleep polysomnograph (GS) was performed by a doctor blinded to the treatment group at the participants' house, using the MediPalm personal recording device (Braebon Medical Corporation, Kanata, Ontario, Canada). The night's sleep PSG included four electroencephalogram channels (C4-A1, C3-A2, O2-A1, O1-A2 []), an electro-oculogram (two channels), a submental electromyogram (EMG), a finger pulse oximetry, an oronasal airflow (oronasaltermisor), a torque and abdominal motion belt (supleum). The participants were not personally supervised. Sharpley et al. [, , ] have shown that the use of homemade sleep recordings provides a reliable means to detect the effects of medications on dream architecture. Once the PSG was applied (approximately 1900 hrs each night of study), a timer was set to record for eight hours after the usual dream or until the participant got up in the morning. The usual sleep time was verbally confirmed for each participant. Participants were asked to retire and increase at their usual time and to abstain from alcohol on nights of study; however, the normal intake of caffeine and nicotine was maintained. While the participants did not all lay at the same time, eight hours or less were enough time to sleep for the subscribers. The clinicians returned in the morning (following the usual sailing time of the participants) to recover the PSG team. Sleep delays were calculated from the lights off. The PSGs were manually marked in 30 seconds according to standardized criteria of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine [], using Pursuit Advanced Sleep System software (Braebon Medical Corporation, Carp, Canada). Ruehland et al. [] have shown that the measurements of the dream architecture are not affected by the number of EEG electrode placements used in the PSG score. The technicians were blinded to the state of treatment. Only a PSG recording was excluded from the analysis due to technical problems. Obstructive and hypopnea apneas, defined as partial obstruction of the airways leading to a 50% reduction in the toracoabdominal movement that lasted at least 10 seconds [], were scored using the American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force [] criteria. The excitations were noted on the basis of criteria of the American Association of Sleep Disorders, 1992 []. The respiratory disorder index (RDI) was calculated, which included apneas, hypopneas and snoria excitations for the number of events per hour of sleep. Statistical analysis The recording of PSGs and clinical measures (with the exception of CGI) were analyzed by an analysis of repeated measures of 2 tracks and 1 track (ANOVA). The design included two treatment groups (placebo × olanzapine) at three time points (baseline, Day 2-4 and Day 28–31). Independent sampling t tests examined post-investigation comparisons. Hedge's g was used to calculate the effect size of the main result measurement, changes in SWS, between groups on 28–31. Lost, clinical, and CANTAB PSG data were replaced by the latest observation carried forward. A participant did not complete any of the CANTAB and was not included for this analysis. Single-tail distributions were used for all clinical measures, while for polysomnographic and neurocognitive measures two-tail distributions were used. In addition, the demographic comparisons between groups were analysed through accurate Fisher or ANOVAs tests (see Table ). In the case of repeated ANOVA measures, trend analysis (contracts) were conducted and reported. Neither the sphericity of the variance nor a significant main effect of the subjective variable is an assumption of analysis of current trends. Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics Sociodemographic characteristicsResultsTwenty-five participants were included in the analysis (N = 15 olanzepines and N = 10 treated placebo). The average age (±SD) of the treated group with olanzapine and of the treated group with placebo was 46 ± 17 years (range: 20-59, median: 45) and 46 ± 9 years (range: 19-79, median: 46), respectively and does not differ significantly between the treatment groups (see Table ). The table summarizes all the primary and secondary measures of polysomnographic results for the architecture of sleep, both in olanzapino groups and in placebo, on base, day 2-4 and day 28–31. The figure shows the percentage of TST spent on SWS and the latency to SWS in olanzapine groups and placebo treated. ANOVA did not produce significant changes in the percentage of TST spent on SWS between the olanzapino-treated group with placebo (F[1,23] =2.36; p = 0,138; Hedge's g = 0.53) over time (F[1,23] =0,256; p = 0.775). Latency to SWS significantly decreased with olanzapine treatment by the end of the trial (no main effect of treatment, F[1,23] = 2.49, p = .128; significant interaction of time x treatment, F[1,23] = 5.49, p = 0.028). Compared to the two treatment groups at each time indicated that at the beginning of the test latency to SWS was no different (t[23] = -.192, p = .849) but by the day 28–31, the Olanzapine treaty group reached SWS faster than the placebo group (t[23] = 2.42, p = 0.024; hedges g = 0.97). Latency to sleep however, was not significantly different and could not account for decreased latency to SWS in the olanzapine treated group (no main effect of treatment F[1,23] = 2.17, p = 0.154 or time F[1,23] = 0.297, p = .591). The duration of the SWS was not significantly affected by the olanzapine treatment compared to the placebo (F[1,23] =0.581; p = 0,454) over time (F[1,23] = 0.00; p = 0.984; Hedge's g = 0,113). Polysomnographic measures Polysomnographic Measures Chart 1 Latency to slow wave sleep and percentage of slow wave sleep. A) Means ± standard error of the mean of latency to delay the wave dream (SWS) in minutes, both for olanzapino groups- and placebo treated for each time. B) Percentage of SWS measured by SWS ratio within total sleep time (TST) in minutes. *p = 0.024 between placebo and olanzapine groups on the 28th–31st. Latency to slow wave sleep and percentage of slow wave sleep. A)B)TST and sleep efficiency are shown in the Figure for Olanzapino groups- and placebo treated. Two repeated bidirectional measures ANOVA showed an increase in TST (tendance for the main effect of treatment, F[1,23] = 3.69, p = 0.067) and sleep efficiency (main effect of treatment, F[1,23] = 5.10, p = 0.034) of the treated group with olanzapine compared to the treated group with placebo. Both TST and sleep efficiency demonstrated significant time x treatment interactions (TST: F[1,23] = 4.58; p = .043; sleep efficiency: F[1,23] = 5.27, p = 0.031). Independent posthoc sampling tests were performed to analyze the nature of these interactions and did not reveal any significant difference in TST or sleep efficiency at the base (TST: t23 = -0.325, p = 0.798; Sleep efficiency: t23 = -0.460, p = 0.65) but per day 28–31 the olanzapine treatment increased significantly both (TST: t23 = -2.21; p = 0.03). Continuity of sleep. A) Total sleep time B) Sleep efficiency. It means ± standard average error for both olanzapino and placebo groups treated. Total sleep time is measured in minutes. Sleep efficiency: % = total sleep time(TST)/time in bed (TIB)× 100. *p The continuity of sleep. (A)B)–As an increase in TST, participants experienced significantly less awakenings (table) and less time waking in general compared to treatment with placebo (2 repeated ANOVA measures pathways; main effect of treatment, number of awakenings, F[1,23] = 10.0, p = 0.004; time of awakening, F[1,23] = 4.8, p = 0.037). The post-hoc analysis of the significant interaction of time by treatment in awake time (F[1,23] = 4.93, p = 0.037) indicated that at the base, the awakening times did not differ between placebo participants and treated with olanzapine (t23 = 0.531, p = 0.601) but by day 28–31, the olanzapine treatment significantly decreases the number of participants in the awakening time experienced (t23 = 2. Repeated two-way ANOVA measures also analyzed the percentage of TST spent on R and the duration of R (Table). There was no main effect of treatment or time in percentage of TST spent on R (F[1,23] = .796, p = 0.3322; F[1,23] = 0.0205, p = 0,875, respectively. There was a significant effect of the olanzapine treatment in the duration of the R (F[1,23] = 4.78, p = 0.0399) however there was no significant effect of time (F[1,23] = .003, p = 0.957) or a significant interaction of treatment over time (F[1,23] = .696, p = 0,413). In addition, the Table means to indicate that the olanzapino group showed more R than the placebo group even in the baseline, suggesting that the difference in sleep R was not due to the addition of olanzapine. MeasuresClinical measures are included as a result of a secondary objective of the study. The figure shows the average scores of MADRS for the participants of the olanzapino- and placebo-treated. Repeated ANOVA in two senses showed no significant differences between olanzapine and placebo treatment for MARDS or HDRS scores (F[1,23] = 1,09, p = .306; F[1,23] = 0,269, p = 609, respectively). However, both MARDS and HDRS decreased significantly over time (F[1,23] = 6.03, p = .022; F[1,23] = 20.0, p = Figure 3 Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale. Total score with average ± standard average error for both olanzapino groups- and placebo treated. *p Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale. Table 3 Clinical measures Clinical Measures Neurocognitive Measures Neurocognitive measures, evaluated as mean scores of CANTAB tests, are shown in Table and were evaluated as a secondary objective of the study. Errors and the score of the strategy of the task of the SWM CANTAB of the olanzapine and placebo groups did not significantly change between the groups (F[1,22] = 0.3, p = 0.590; F[1,22] = 0,588, p = 0,426, respectively) or over time (F[1,22] = 1.4, p = 0,242; F[1,22] = 0.77, respectively). The average length of the space recalled in the task of the SSP CANTAB was also not significantly different between the treatment groups or over time (2 repeated measures via ANOVA, F[1,22] = 0.102, p = 0.753; F[1,22] = 0.036, p = 0.852, respectively). Finally, the average reaction time and the movement time of the CANTAB RTI task for the olanzapino- and placebo-treated groups also did not show significant changes as a result of the olanzapine treatment (2-repeated measures ANOVA reaction time and movement: treamtment, F[1,22] = 0.089, p = .768; F[NOV1,22] = 0.15, p = .702, respectively, Table 4 Cognitive measures Cognitive Measures Debate Surprisingly, the addition of olanzapine to the current drug regimes of patients who experience major unipolar or bipolar depressive episodes only led to significant improvements in latency to SBS, but not in other USG measures, the main result measure of this study. However, the increase in olanzapine significantly improved the sleep continuity of the secondary result, which included sleep efficiency, the number of awakenings, the time spent awake and the total time of sleep. These improvements did not extend to significant changes other aspects of the dream architecture, as a percentage of dream R. Olanzapine treatment also significantly improved the severity of the disease without changes in the measures of the executive and psychomotor function. To date, Sharpley et al. [] have reported the only study to investigate the addition of olanzapine treatment to SSRI on night-to-morning polysomnograph in patients with MDD-resistant treatment. They showed significant improvements in sleep efficiency, total sleep time, percentage of time awake, total N percentage, subjective sleep quality, a decrease of R percent, and an increase in latency R after a single dose of olanzapine. Our study revealed similar improvements only for sleep continuity measures and the severity of the disease. We have observed similar improvements in HDRS scores. The study of Sharpley et al. [] included only patients with resistant treatment (to the SSRI DDD) and olanzapine was administered with an open label without control or comparison group. In comparison, in our randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled study, both patients with MDD and BD were included, with most patients who were recommended to receive increased antidepressant treatment being resistant to treatment with SSRI. Thus, conflicting results can be due to differences in the populations studied and methodology. Antidepressants rarely improve sleep continuity; most improvements are seen with tricyclic antidepressants. An increase in total sleep time and sleep efficiency was observed, as well as a decrease in sleep latency and total sailing time here, similar to the view with other agents of increase such as risperidone [], but different from quetiapina, which does not alter sleep continuity in depression []. The beneficial effects of olanzapine treatment on sleep continuity can be due to its diverse pharmacological profile. Mostly, olanzapine is an antagonist of 5-HT2A/C receptors, 5-HT3 and 5-HT6 []. A reduction in serotonin firing rates allows the first sleep cycle to occur and serotonin suppresses sleep R by inhibiting promotant colinergic neurons R []. Olanzapine can also promote normalization of sleep through the antagonism of hyperactive colinergic neurons, as olanzapine has affinity for M1-M5 muscarinic receptors. Scenic neurons are responsible for the initial activation and the continuous generation of sleep R []. Olanzapine also has moderate affinity for the α-adrenergic1 receptor. The adrenergic system plays a role in suppressing R and promoting sleep cycles []. Finally, the olanzapine also has affinity for histamine receptor1. Histamine is thought to promote the awakening and reductions of histamine allow sleep to occur []. Therefore, the effects of olanzapine on the neurotransmitter systems important for normal sleep continuity probably caused improvements in reported sleep continuity. Few medicines have been proven reliable to improve SBS in the treatment of unipolar or bipolar depression. Only a randomized controlled trial (RCT) was identified that examines the effects of sleep trazodone using polysomnography. A study conducted by Saletu-Zyhlarz et al. [] examined insomnia patients with dystymy and reported that the administration of trazodone significantly increased latency to stage 3, time and percentage at stage 3, sleep efficiency and number of awakenings. A significant increase in the amount and percentage of sleep was also observed R. Bemmel et al. [] performed a unique blind study of trazodone treatment in sleep architecture in patients with MDD. They reported no improvements to SWS and significant R suppression. On the other hand, Mouret et al. [] examined the effects of open-ended label trazodone in sleep patients with MDD and reported significant improvements in SWS and no effect on sleep R. A study by Kluge et al. [] examined the effects of the open label of duloxetine on sleep in MDD, and reported a significant improvement in latency to SWS and time in SWS. Significant R suppression was reported. RCTs were not identified on the effects of duloxetine. Antidepressants repress sleep R reliably; however, their effects on SWS are inconsistent in treating major depressive episodes. Almost all antidepressants have shown to suppress sleep R by increasing latency to R and decreasing the total duration of sleep R. Removal R was not seen in this study. Although expected, the lack of R suppression may be due to the participants' concomitant medications. Only three participants were not taking any other medications, 80% of the participants took at least one antidepressant, one participant was taking only one benzodiazepine, and one participant only took litio. More than 50% of participants were taking more than one medication in the study's enrollment. Antidepressant medications and lithium may have suppressed sleep R and, therefore, additional deletion of sleep R with the addition of olanzapine may have been too minimal to detect. Although previous RRS enhancement studies have shown the suppression of R, the degree of polypharmacy was lower in these studies, since each participant was only taking an antidepressant []. This can reflect the often seen changes with psychotropic treatment to the dream architecture [, ]. Few medicines have been proven reliable to suppress sleep R and also increase sleep continuity and SWS. Many medicines, especially antidepressants, suppress sleep R and have no harmful effects or harmful effects on sleep continuity or SBS. In addition, a number of strategies have been demonstrated, including olanzapine, to improve sleep continuity and SWS and have no effect on R sleep. Therefore, it is plausible that the abolition R and other changes in the dream architecture are due to separate underlying mechanisms and may need to be treated separately. The improvement of the depressive symptoms observed in this study is representative of the effects of other atypical antipsychotic agents in the treatment of depression, as the olanzapino group had a significantly higher improvement than the placebo in the MADRS score. The power of the study, however, was not such as determining effectiveness. The clinical response was observed in 46% of patients treated with olanzapine, while only 20% of patients treated with placebo did so. Twenty-six per cent of participants treated with olanzapine came to remission and less than half (10%) in the placebo group did so. The response rates reported earlier in a randomized double-blind study of the olanzapine/fluoxetin combination for the treatment of depression are similar to what is observed here []. A significant improvement in depressive symptoms with a combination of olanzapine/fluoxetin versus placebo has also been reported in the treatment of bipolar disorder. [] Literature on cognitive function in depression is quite diverse and conflictive, since it seems that there is no clear pattern of dysfunction in MDD [, , ]. The lack of changes seen here in the work memory or the psychomotor function was not unexpected. The deficiencies observed in neurocognitive tests in depression may be due to lack of motivation to complete the task with precision and therefore psychotropic treatment or sleep normalization would not have an effect on this beyond the improvement of depressive symptoms. As only 26% of our participants came to remission, many participants had residual depressive symptoms and could not have had an improvement in motivation. The lack of a normal control group prevents us from reporting whether the level of operation of the base is within the normal range or is deteriorated and did not improve with the treatment. There are a number of limitations in this study. First, the participants stayed in a wide variety of concomitant drugs. This probably contributed to the very variable effect of olanzapine in SWS. Second, there were a large number of secondary measurements of results and a relatively small sample size. This is more relevant to the lack of change seen in SWS, R sleep and neurocognitive measures. A larger sample size can also be given to a more accurate differentiation between placebo and olanzapine participants treated on improvements in the quality of the subjective sleep. In addition, the duration of this study only allowed the evaluation of the short-term treatment of depression; it is well understood that observing the total improvement with many psychotropic drugs different from 6 to 8 weeks or even more is necessary. Finally, the results of this study are generalizable to a select number of patients' populations, as there were some assorted exclusions and a variety of concomitant drugs. For example, the results of this study do not allow us to understand what effect olanzapine may have in the dream architecture in patients with abuse of wild substance. More studies are needed to assess the influence of different doses and long-term studies to see if improvements continue to maintain treatment. Conclusions The increase in olanzapine in the treatment of unipolar and bipolar depression led to significant improvements in sleep continuity, total sleep time and latency at the beginning of sleep, as well as a significantly improved depressed mood. However, significant changes were only moderately seen in SWS and not at all in sleep R. Olanzapine has shown to increase SBS in other psychiatric disorders, for example schizophrenia []. Factors as simple as the dose of olanzapine can moderately affect SWS through patient populations. In addition, even within the populations of patients much of the literature shows conflictive results [–] of olanzapine on the architecture of sleep. No changes were observed in cognition, both in working memory and in psychomotor function. However, olanzapine may be one of the few drugs that improve sleep continuity, so it focuses directly on symptoms of depression. Olanzapina can produce this effect through its high affinity not only for serotonin receptors but also muscarinic, adrenergic and hysterical receptors. The heterogeneity of this study population allows the generalization of clinical populations, and as such olanzapine can be an effective tool in the treatment of sleep dysfunction in depression. Absorbing of the score of the depression Montgomery-asberg Automated Neuropsychological Test Battery at CambridgeSpatial WorkflowReaction time Greater depressive disorder Bipolar disorder Quick-eyed movement Non-drip sleep rateFull-stage reading ReferencesReite M, Ruddy J, Nagel K: Evaluation and Management of Sleep Disorders. 2002, Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Editorial, 3 Ford DE, Kamerow DB: Epidemiological study of sleep disorders and psychiatric disorders: An opportunity for prevention? JAMA. 1989, 262: 1479-1484. 10.1001/jama.1989.03430110069030. Chang PP, Ford DE, Mead LA, Cooper-Patrick L, Klag MJ: Insomnia in young men and later depression: The study of Johns Hopkins precursors. Am J Epidemiol. 1997, 146: 105-114. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009241. Dew MA, Reynolds CF, Houck PR, Hall M, Buysse DJ, Frank E, Kupfer D: Temporary Profiles of the Depression Course During Treatment: Road Preachers for Recovery in the Elders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997, 54: 1016-1024. 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230050007. Reynolds CF, Frank E, Houck PR, Mazumdar S, Dew MA, Cornes C, Buysse D, Begley A, Kupfer D: What older patients with remitted depression stay well with interpersonal psychotherapy continuing after the interruption of antidepressant medication?. Am J Psychiatry. 1997, 154: 958-962. Markov D, Goldman M: normal sleep and circadian rhythms: underlying neurobiologic mechanisms sleep and awakening. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2006, 29: 841-853. 10.1016/j.psc.2006.09.008. Hirshkowitz M: Normal human dream: A general vision. Med Clin North Am. 2004, 88: 551-565. 10.1016/j.mcna.2004.01.001. vii Riemann D, Berger M, Voderholzer U: Sleep and depression are the results of psychobiological studies: a general vision. Biol Psychol. 2001, 57: 67-103. 10.1016/S0301-0511(01)00090-4. Kupfer DJ, Harrow M, Detre T: Sleep patterns and psychopathology. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1969, 45: 75-89. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1969.tb06203.x. Kupfer DJ, Foster FG: Interval between the start of sleep and the rapid movement of sleep as a depression indicator. Lancet. 1972, 300: 684-686. 10.1016/S0140-6736(72)92090-9. Kupfer DJ, Foster FG, Reich L, Thompson SK, Weiss B: EEG sleep changes as predictors of depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1976, 133: 622-626. Benca RM, Obermeyer WH, Thisted RA, Gillin JC: psychiatric and sleep disorders: A meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992, 49: 651-668. 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080059010. Sharpley AL, Attenburrow ME, Hafizi S, Cowen PJ: Olanzapina increases the slow-wave dream and sleep continuity in depressed SSRI-resistant patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005, 66: 450-454. 10.4088/JCP.v66n0407. Sweeney JA, Kmiec JA, Kupfer DJ: Neuropsychological needs in bipolar and unipolar mood disorders in the CANTAB neurocognitive battery. Biol Psychiatry. 2000, 48: 674-684. 10.1016/S0006-3223(00)00910-0. Gruber S, Rathgeber K, Braunig P, Gauggel S: Stability and course of neuropsychological deficits in manic and depressed bipolar patients compared to patients with major depression. J Affect Disord. 2007, 104: 61-71. 10.1016/j.jad.2007.02.011. Elliott R, Sahakian BJ, McKay AP, Herrod JJ, Robbins TW, Paykel ES: Neuropsychological needs in unipolar depression: the influence of perceived failure on subsequent performance. Psychol Med. 1996, 26: 975-989. 10.1017/S0033291700035303. Grant MM, Thase ME, Sweeney JA: Cognitive disorder in young outcast adults: evidence of modest deterioration. Biol Psychiatry. 2001, 50: 35-43. 10.1016/S0006-3223(00)01072-6. Purcell R, Maruff P, Kyrios M, Pantelis C: Neuropsychological function in young patients with greater unipolar depression. Psychol Med. 1997, 27: 1277-1285. 10.1017/S0033291797005448. Nilsson JP, Soderstrom M, Karlsson AU, Lekander M, Akerstedt T, Lindroth NE, Axelsson J: Less effective executive operation after a night of sleep deprivation. J Sleep Res. 2005, 14: 1-6. 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2005.00442.x. Chee MW, Chuah LY: Functional neuroimaginous insights on how sleep and sleep deprivation affect memory and cognition. Curr Opin Neurol. 2008, 21: 417-423. Jones K, Harrison Y: frontal lobe function, loss of sleep and fragmented sleep. Sleep Med Rev. 2001, 5: 463-475. 10.1053/smrv.2001.0203. Banks S, Dinges DF: Behavioral and physiological consequences of sleep restriction. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007, 3: 519-528. Ferrara M, De GL, Casagrande M, Bertini M: The selective sleep deprivation of slow wave and the effects of night time on cognitive performance when waking. Psychophysiology. 2000, 37: 440-446. 10.1111/1469-8986.3740440. Ferrara M, De GL, Bertini M: The effects of slow-wave sleep deprivation (SWS) and night time on behavior when waking up. Physiol Behav. 1999, 68: 55-61. 10.1016/S0031-9384(99)00150-X. Naylor E, Penev PD, Orbeta L, Janssen I, Ortiz R, Colecchia EF, Keng M, Finkel S, Zee PC: Daily social and physical activity increases slow-wave sleep and diurnal neuropsychological performance in the elderly. Sleep. 2000, 23: 87-95. Göder R, Boigs M, Braun S, Friege L, Fritzer G, Aldenhoff JB, Hinze-Selch D: The deterioration of visuospatial memory is associated with a decrease in the sleep of slow wave in schizophrenia. J Psychiat Res. 2004, 38: 591-599. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.04.005. John J, Wu MF, Boehmer LN, Siegel JM: Cataplexy-active neurons in hypothalamus: implications for the role of histamine in sleep and awakening behavior. Neuron. 2004, 42: 619-634. 10.1016/S0896-6273(04)00247-8. Wu MF, Gulyani SA, Yau E, Mignot E, Phan B, Siegel JM: Locus coeruleus neurons: cessation of the activity during the cataplexy. Neuroscience. 1999, 91: 1389-1399. 10.1016/S0306-4522(98)00600-9. Saper CB, Chou TC, Scammell TE: Sleep switch: hypothalamic sleep control and awakening. Neurosci Trends. 2001, 24: 726-731. 10.1016/S0166-2236(00)02002-6. Szymusiak R: Magnocellular cores of the basal antebrain: sleep substrates and excitation regulation. Sleep. 1995, 18: 478-500. Sharpley AL, Cowen PJ: Effect of pharmacological treatments in the sleep of depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry. 1995, 37: 85-98. 10.1016/0006-3223(94)00135-P. Shelton RC, Tollefson GD, Tohen M, Stahl S, Gannon KS, Jacobs TG, Buras WR, Bymaster FP, Zhang W, Spencer KA, Feldman PD, Meltzer HY: A novel upsurge strategy to treat tough main depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2001, 158: 131-134. 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.1.131. Bymaster FP, Rasmussen K, Calligaro DO, Nelson DL, DeLapp NW, Wong DT, Moore NA: In vitro and in vivo olanzapine biochemistry: a new atypical antipsychotic drug. Psychiatry J Clin. 1997, 58: 28-36. Landsness EC, Goldstein MR, Peterson MJ, Tononi G, Benca RM: Antidepressant effects of selective slow-wave sleep deprivation in the main depression: A high-density EEG research. J Psychiatr Res. 2011, 45: 1019-1026. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.02.003. Manber R, Edinger JD, Gress JL, San Pedro-Salcedo MG, Kuo TF, Kalista T: Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia improves the result of depression in patients with comorbid major depressive disorder and insomnia. Sleep, 2008, 31: 489-495. Thase ME, Corya SA, Osuntokun O, Case M, Henley DB, Sanger TM, Watson SB, Dube S: Randomized and double-blind comparison of the olanzapine/fluoxetin combination, olanzapine and fluoxetin in severe treatment-resistant depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007, 68: 224-236. 10.4088/JCP.v68n0207. Shopping DJ, Kupfer DJ, Frank E, Monk TH, Ritenour A, Ehlers C: Electroencephalographic sleep studies in depressed outpatients treated with interpersonal psychotherapy. I. Reference studies in response and non-response. Psychiatry Res. 1992, 40: 13-26. Salin-Pascual RJ, Galicia-Polo L, Drucker-Colin R: Sleep changes after 4 consecutive days of administration of venlafaxine in normal volunteers. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997, 58: 348-350. 10.4088/JCP.v58n0803. Wiegand M, Riemann D, Schreiber W, Lauer CJ, Berger M: Morning and afternoon naps in depressed patients after total sleep deprivation: sleep structure and impact in mood. Biol Psychiatry. 1993, 33: 467-476. 10.1016/0006-3223(93)90175-D. Sharpley AL, Vassallo CM, Cowen PJ: Olanzapine increases the dream of slow wave: evidence for blocking the 5-HT(2C) in vivo central receptors. Biol Psychiatry. 2000, 47: 468-470. 10.1016/S0006-3223(99)00273-5. Lindberg N, Virkkunen M, Tani P, Appelberg B, Virkkala J, Rimon R, Porkka-Heiskanen T: Effect of a unique dose of olanzapine on sleep in healthy and male females. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002, 17: 177-184. 10.1097/00004850-200207000-00004. Sharpley AL, Vassallo CM, Pooley EC, Harrison PJ, Cowen PJ: Alélic variation in the 5-HT2C receptor (HT2RC) and the increase in the slow-wave dream produced by olanzapine. Psychopharmacology. 2001, 153: 271-272. 10.1007/s002130000553. Meltzer HY, McGurk SR: The effects of chlorzapine, risperidone and olanzapine on cognitive function in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1999, 25: 233-255. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033376. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 1994, Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 4 Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar G: The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998, 59: 22-33. Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA: A qualification scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978, 133: 429-435. 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. Hamilton M: A qualification scale for depression. Psychiatry of Neurosurgery J. 1960, 23: 56-62. 10.1136/jnp.23.1.56. Montgomery SA, Asberg M: A new scale of depression designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979, 134: 382-389. 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. Hamilton M: Assessment of rating anxiety states. Br J Med Psychol. 1959, 32: 50-55. 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x. Hamilton M: Diagnosis and anxiety rating. Br J Psychiatry. 1969, Special Pub 3: 76-79. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ: The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new tool for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28: 193-213. 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. Dixon JS, Bird HA: Reproductibility along a 10 cm vertical visual analogue scale. Ann Rheum Dis. 1981, 40: 87-89. 10.1136/ard.40.1.87. Johns MW: A new method to measure daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleep scale. Sleepy. 1991, 14: 540-545. Guy W: Global clinical trials. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, revised. Edited by: Guy W. 1976, Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health Lawrence AD, Sahakian BJ: The Neuropsychology of Frontostriatal Dementia. Manual of Clinical Psychology of Ageing. Edited by: Woods RT. 1996, New York: Wiley, 243-265. Robbins TW, James M, Owen AM, Sahakian BJ, McInnes L, Rabbit P: Cambridge Neuropsychological Automated Test Battery (CANTAB): A factorial analytical study of a large sample of normal senior volunteers. Dementia. 1994, 5: 266-281. Bonnet A, Carley D, Carskadon M, Easton P, Guilleminault C, Harper R, Hayes B, Hirshkowitz M, Ktonas P, Keenan S, Pressman M, Roehers T, Smith J, Walsh J, Weber S, Westbrook P: EEG arousals: scoring rules and examples: A preliminary report from the Atlas Sleep Disorders Task Force. Sleep. 1992, 15: 173-184. Sharpley AL, Williamson DJ, Attenburrow ME, Pearson G, Sargent P, Cowen PJ: The effects of paroxetine and nefazodone in sleep: a placebo-controlled trial. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1996, 126: 50-54. 10.1007/BF02246410. Sharpley AL, McGavin CL, Whale R, Cowen PJ: Antidepressant Effect of Hypericum Piercing (the St.John's Weed) in the sleep polysomnogram. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1998, 139: 286-287. 10.1007/s002130050718. Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson A, Quan SF: The AASM Manual for Sleep Gathering and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. 2007, Weschester: American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 1 Ruehland WR, O'Donoghue FJ, Pierce RJ, Thornton AT, Singh P, Copland JM, Stevens B, Rochford PD: The 2007 AASM recommendations for the placement of EEG electrodes in polysomnography: Impact on sleep and cortical excitation score. Sleep. 2011, 34: 73-81. Gould GA, Whyte KF, Rhind GB, Airlie MAA, Catterall JR, Shapiro CM, Douglas NJ: Sleep hypopnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1988, 137: 895-898. American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force: Adult-Related Respiratory Diseases: Recommendations to define syndrome and measurement techniques in clinical research. Sleep. 1999, 22: 667-689. Cohrs S, Meier A, Neumann AC, Jordan W, Ruther E, Rodenbeck A: Improved sleep continuity and increased slow-wave sleep and REM latency during the treatment of zippered: a randomized, controlled and cross-sectional trial of 12 healthy male subjects. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005, 66: 989-996. 10.4088/JCP.v66n0805. Gedge L, Lazowski L, Murray D, Jokic R, Milev R: Effects of quetiapine on dream architecture in patients with unipolar or bipolar depression. Neuropsychiatrist Dis Treat. 2010, 6: 501-508. Saletu-Zyhlarz GM, Abu-Bakr MH, Anderererer P, Semler B, Decker K, Parapatics S, Tschida U, Winkler A, Saletu B: Insomnia related to dystimia: polysomnographic and psychometric comparison with normal controls and acute therapeutic tests with trazodone. Neuropsychobiology, 2001, 44: 139-149. 10.1159/000054934. Bemmel AL, Havermans RG, Diest R: Trazodone effects in EEG sleep and clinical status in major depression. Psychopharmacology. 1992, 107: 569-574. 10.1007/BF02245272. Mouret J, Lemoine P, Minuit MP, Benkelfat C, Renardet M: Trazodone effects in the sleep of depressed subjects – a polygraphic study. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1988, 95 (Suppl.): S37-S43. Kluge M, Schussler P, Steiger A: Duloxetine increases stage 3 sleep and suppresses rapid eye movement (REM) sleeps in patients with major depression. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007, 17: 527-531. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.01.006. Sharpley AL, Bhagwagar Z, Hafizi S, Whale WR, Gijsman HJ, Cowen PJ: Risperidone's increase decreases the sleep of the rapid eye movement and decreases awakening in depressed treatment-resistant patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003, 64: 192-196. 10.4088/JCP.v64n0212. Kupfer DJ, Reynolds CF, Weiss BL, Foster FG: Lithium carbonate and sleep in affective disorders: further considerations. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1974, 30: 79-84. 10.1001/archpsyc.1974.01760070061009. Dube S, Tollefson GD, Thase ME, Briggs SD, Van Campen LE, Case M, Tohen M: Inauguration of anti-depressant effect of the olanzapine and olanzapine/fluoxetin combination in bipolar depression. Disord bipolar. 2007, 9: 618-627. 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00491.x. Taylor Tavares JV, Clark L, Cannon DM, Erickson K, Drevets WC, Sahakian BJ: Profiles other than neurocognitive function in unipolar inmedicated depression and bipolar depression II. Biol Psychiatry. 2007, 62: 917-924. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.034. Weiland-Fiedler P, Erickson K, Waldeck T, Luckenbaugh DA, Pike D, Bonne O, Charney DS, Neumeister A: Evidence for continuing neuropsychological impairments in depression. J Affect Disord. 2004, 82: 253-258. 10.1016/j.jad.2003.10.009. Kluge M, Schacht A, Himmerrich H, Rummel-Kluge C, Wehmeier PM, Dalah M, Hinze-Selch D, Kraus T, Dittmann RW, Pollmacher T, Schuld A: Olanazpine and clozapine differently affect sleep in patients with schizoprhrenia: Results of a double-blind, polysomnographic and literature review. Schizophr Res. 2014, 152: 255-260. 10.1016/j.schres.2013.11.009. Pre-publication history The pre-publication history of this document can be accessed here: Recognition Special thanks to Dr. Lawson for his valuable advice and statistical support. Thanks to Alan Lowe for the project assistance. Thanks to all MDRTS staff who made this project possible, especially Teresa Garrah, Judy Joannette, Liane Tackaberry, Ann Shea, Dr. Aldaoud and Dr. DeAngelis, and all the participants. Author's information Affiliates Centre for Neuroscience Studies, Queen's University, Kingston, CanadaLauren K Lazowski & Emily R Hawken Department of Psychology, University of Carleton, Ottawa, CanadaBen Townsend Department of Psychiatry, University of Queen, 752 King Street West, Kingston, ON K7L 4X3, CanadaEmily R Hawken, Ruzica Jokic, Regina du Toit You can also search this author in You can also search this author in You can also search this author in You can also search this author in You can also search this author in Correspondence to the correspondent . Additional Information Competing interests The study was funded by a research grant from Eli Lilly Canada, which was awarded to L. Lazowski under the supervision of Dr. R. Milev. BT, ERH, RJ RT states that they have no competing interests. Contributions by LL authors contributed substantially to the design and design, data acquisition, article drafting and final approval of the version to be published. BT contributed substantially to the analysis and interpretation of the data, the drafting of the article and gave the final approval of the version to be published. ERH contributed substantially to data analysis and interpretation, critically revised it for important intellectual content and gave the final approval of the version to be published. RJ contributed substantially to the design and design, data acquisition, article drafting and gave the final approval of the version to be published. RT contributed substantially to the design and design, data acquisition, article drafting and gave the final approval of the version to be published. RM contributed substantially to design and design, critically revised it for important intellectual content and gave the final approval of the version to be published. Original files presented by the authors for images Below are the links to the original files presented by the authors for images. Rights and Permits About this article Cite this article Lazowski, L.K., Townsend, B., Hawken, E.R. et al. Sleep architecture and cognitive changes in patients treated with olanzapine with depression: A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 14, 202 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-20214, Received: 17 July 2013 Accepted: 10 July 2014Published: 17 July 2014DOI: Palabras clave Associated contentSelectionWarning BMC Psychiatry ISSN: 1147234XContact us By using this website, you agree to our , , and politics. We use at the center of preferences. © 2021 BioMed Central Ltd unless otherwise indicated. Part of .

User reviews of Olanzapine to treat Insomnia Also known as: Zyprexa, Zyprexa Zydis, Intramuscular Zyprexa, Zyprexa Relprevv Olanzapine has an average score of 6.8 out of 10 out of a total of 60 ratings for Insomnia treatment. 52% of the users who reviewed Olanzapine reported a positive effect, while 18% reported a negative effect. Olanzapine Rating Summary6.860 user reviews. Compare all 80 medicines used in the . 10 23% 9 17% 8 12% 7 17% 6 2% 5 8% 4 3% 3 2% 2 0% 1 17% Comments for Olanzapine "This medicine is an absolute lifeline. I was so afraid to try it and I've been on a list of other medications for insomnia and nothing worked. I went from having interrupted the shallow sleep for a couple of hours every night to sleep all night, waking up after 8-9 hours without feeling rested without any side effect other than a very mild sleep of the day that is an exchange that I am more than willing to accept right now. Try this if you're in the fence. I'm taking 5 mg at night and that dose works like a charm for me. " 10 "I was in olanzapine for three years. It worked well for me. However, the weight gain was terrible. I'm a healthy dining room, but I've won 40 pounds. I've got cerebral palsy and I've got a stick. It came to the point where I put so much weight when I fell, I couldn't get up. However, it's fantastic to sleep. " 8 "Prescribed 5 mg olanzapine tablets to withdraw from zopiclone after severe anxiety and insomnia. I have nothing but praise for olanzapine - it gives you a quiet feeling that allows you to sleep naturally. Not after the effects on the low dose. 5 mg is enough for a man of 13 stones in my case. I only received this prescribed by my primary mental health team, as doctors seemed happy to prescribe Z medications that left me dependent on them to sleep. " 9 "My best friend was at 10 mg of Olanzapina for 25 years. He made the decision to leave her with the doctor's guide because she caused her diabetes and was making her diabetes worse. I'm also in Olanzapine and my friend told me that he'll be the guinea pig and I'll get him out first and if it's okay then I'll know how to get out of it. He got off her 4 months ago and her insomnia was so bad he left 4 months with just any dream at all. The doctor prescribed hydroxyzine for his insomnia but it didn't work. My friend couldn't sleep and was very sick of not sleeping and was so confused. He took his life and died on August 8, 2020 as a result. I lost my best friend by olanzapine. " 1 "Symptoms of terrible abstinence. I was in olanzapine for insomnia for only 12 days. After stopping, I had 2 weeks of abstinence symptoms nausea, fatigue, flu as symptoms, brain fog and more than a week of insomnia. My brain doesn't know how to sleep without this drug and it works very hard to regain the ability to sleep on its own. Even in her I didn't have a good dream, I went to bed at 11:00 until 2:00 in the morning and then slept until 11am. He made me a zombie while I was in it. Stay away from this horrible drug!!! 1 "I have used Olazapine 2.5 mg (dosage one) for years. It works great for me, it gives me a good 8 - 10 hours sleep a night without waking up all night and I always wake up feeling like I've had a great night of sleep. Don't get off by the fear tactics of other 2.5 mg or 5 mg revisers affect the same neurotransmitters but only slightly. You will not develop psychosis when you start taking this medication or when you stop taking it. I have stopped and started Olanzapine many times and I have no problem, no mood change (it really helped improve some anxiety problems). Just be careful with weight gain but at a low dose you will barely gain weight, and if you eat healthy and exercise you will be more than good. " 10 "Before I started taking Olanzapina I couldn't sleep properly losing a lot of sleep. In fact, it would be 72 hours without a dream. Now I sleep 9 hours all night. It's a miraculous drug. If you can't sleep properly I recommend taking Olanzapine. " 9 "Take this olanzapine medicine for about 2 and 1/2 months. I was suicidal anxious when my psychiatrist decided to try. He's made me very tired during the first few days, but he's almost eliminated my anxiety and helped me sleep better. Over time, however, I began to decrease the returns to even 10 mg, along with the feeling that I was becoming more foolish ( having trouble focusing, trying to remember certain words)... It just made me dirtier and depressed. He decided to leave her and did not notice until a few days after she was having bad retirements (nausea, anxiety, worse sleep). I wouldn't recommend this medication. I'm trying to conquer my severe depression and poor sleep and this is making it all worse. Even cutting small pieces to the tape barely helps. I wish it never started. " 1 "If you want to have zero quality of life I urge you to take olanzapine. I was prescribed this horrible drug only for insomnia. During the first 6 months I was sedated, then I began to develop horrible side effects (inability to swallow, restlessness, anxiety, being in a zombie state, etc.). Eventually I've developed a tolerance so it didn't help me sleep either. Sadly, I know others who have taken this medication that have developed permanent disorders of movement and brain damage. It effectively jumps neurotransmitters into your brain. After stopping this cold drug turkey because I couldn't swallow anything, I've been left with 9 months of 0-2 hours sleep. This drug will ruin your life. Look at all the lawsuits against Eli Lilly. They warned you. I wish it had been! 1 "Zyprexa is not a sleeping medicine and should not be prescribed for sleep problems. It is a powerful antipsychotic approved and used for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. It is one of the most powerful, if not the most powerful antipsychotic. Once in it, in most cases, it is practically impossible to get out of it. Psychiatrists and other doctors are told that they have no addictive or withdrawal effects. Once in Zyprexa, most people can't go out without major side effects. psychiatrists call this discontinued syndrome, but for lay people, it is no different from withdrawal. At first, it will help your dream and eventually lose your power, requiring more and more dangerous amounts of a drug that affects chemicals miriated in the brain and has been shown to contract brain tissues. Do your research. Be very careful. " "I had an erroneous diagnosis of bipolar and I'm sure the insomnia started at the time I recorded it. I was on it for over a year and insomnia has lasted two years. I am frustrated to see other people here have had bad experiences and side effects are similar and had bad withdrawals, but the Doctors never validate me when I ask you if Olanzipine was the reason for this chronic insomnia or to take responsibility that the reason why he is still sick could be the drugs they prescribed and not the poor sleep hygiene. Now I have become private but I doubt that someone will tell me the truth and more drugs will be prescribed to combat the problems of which were the cause in the first place. All I needed was a therapy that I got in the NHS, but the legacy of the maldiagnosis and all powerful drugs has ruined my life and I can't even work. I don't even have a mental health diagnosis other than insomnia. " 1 "I suffered from early childhood insomnia. Not until completely psychotic did any drug work. I don't think he slept at all for 5 days at 18 years. Then I got zyprexa 5mg. I slept. Unfortunately a few days later I didn't sleep for 3 days. Now given 10 mg of zyprexa. I slept. This cycle continued to 20 mg. Since then 17 years ago, I have weaned 7.5mg. An awakening has occurred in the brand of 7.5 mg. This is the most stable I've ever been. Through diet, exercise and lifestyle options. If you are advised to take olanzapine make sure your psychiatrist knows everything about your health. Sleep, diet, drug abuse, any recent event of the trigger, etc. is a difficult way" 7 "Prescribed 2.5 mg for anxiety and insomnia. He helped a lot at first, after several months of sleep problems returned. Anxiety started to get worse. I tried to slow down my dose and anxiety and insomnia got worse than ever. After 2 years I began to have symptoms of late dyskinesia and tremor. And he never feels rested. My dream was very light, not deep. He tried to reduce the dose again, but he couldn't sleep at all and had unbearably intense anxiety. 4 years later I am trapped in this horrible medication, just sleeping at all, high anxiety, slow brain, with tardiva dyskinesia. Before taking olanzapine my only problem was mild and insomnia anxiety. This drug causes permanent damage. This drug ruined my life. " 1 "Return to leave another review after being in olanzapine for a couple of months. I started taking 10 mg now I take 15 mg. So the subject that was so afraid was to gain weight. When I started taking it I had 80 pounds, very sick and unhealthy. It helped me recover my normal weight, back to 100-105 pounds. Apart from when I started taking it, it has no longer had any effect on my hunger or weight. I think it can cause weight gain if you allow it too. If you exercise, and eat the normal weight gain should not be a problem for you. The reason I realize this is because it makes me hard to get up and go like before I take this drug, but I'd pick it up for a night without sleeping any day. " 9 "Very good to sleep! Olanzapine is a great alternative to help you sleep addictive. I take 5 mg at night and sleep 8 - 10 hours without waking up all night (I used to sleep 5 - 6 hours and wake up several times). During the first few weeks you will be stunned and hungry, but these side effects will disappear. I've been to Olanzapine for 3 months and it's still working well for sleep. " 10 "Zyprexa gives me the best dream ever, but I am constantly tired and makes me so uncontrollably hungry. You just have to be careful what you eat. It also helps my mood, as I also have bipolar disorder. I'd recommend it if you can't really sleep and have bipolar and/or ocd disorder. " 9 "For years I suffered from insomnia. My doctors tried the amnzos and antihistamine antidepressants serocuela and nothing worked for me. I saw a new doctor who put me ten milligrams of Olanzapine and it was a success. Now I'm at 20 mg at night. It puts me to sleep but hunger and weight gain is severe. " 7 Zyprexa (olanzapina): "This medicine is the best sleep help I have found. I tried Ambien and he drove me crazy. I can sleep with Zyprexa and wake up the next morning without side effects. I just have to make sure I take it early at night. If I take it too late, I'm gonna get a dick in the morning. Unlike some of the reports I've heard, it doesn't affect my weight at all. " Zyprexa (olanzapina):10 "I have been diagnosed with a mood disorder and possible bipolar disorder. I was recently put in zyprexa 10 mg 1×daily. Is this addictive to medicine? I also experience severe anxiety and paranoia. What would you say is my problem? I need help! 8 "For side effects, how about dreaming? Now I have long dreams, fun part of this drug. However, I would like to have another way of sleeping because the other side effect of the olanzapine is getting fat which is horrible. " 7 Zyprexa (olanzapina): "Usé Zyprexa (2.5mg) at night for insomnia caused by anxiety and obsessive thoughts. It's the only thing that helped me sleep that's not addictive and it really worked. It also helped my appetite because when I don't sleep well I don't feel like eating a lot either. This medicine also helped with that. Unfortunately I can't use it often because it causes my blood sugar to shoot high sky and I don't like the risk of late dyskinesia. I only take a very small dose when I haven't slept in a while. " Zyprexa (olanzapina):6 Zyprexa (olanzapina): "It was definitely a love/abortion relationship with Zyprexa. I've tried virtually all the sleeping medications available, and it was one of the best because it didn't just put me to sleep, but I also KEPT sleep for 8 hours. It started at 2.5 mg, then 5 mg, " eventually 7.5. Although it took a long time to start, so I had to take it two hours before bed. But like everyone who takes this, I've gained weight. But I found the 1 way that you can really lose weight in this medication, which is to combine exercise with Atkins' diet (low-carb). Zyprexa gives you metabolic syndrome. You no longer burn carbohydrates, which means that all carbohydrates you eat become body fat, so you get fat on this material (so you have to stop eating carbohydrates). I got out of this drug after 1 year. " Zyprexa (olanzapina):5 "I have to have another way of sleeping, meditating and a good exercise and diet routine, however when I took this medication sleep, I don't really want it but it's the only salvation, now I'm fat and only a month has passed. But I sleep! 5 Zyprexa (olanzapina): "This medicine is a God sent. I have tried all the sleeping pills in the book (Ambien, Trazodone, Seroquel, Elavil, ETC.) None of them would keep me asleep all night. 10 mg of this and I sleep like a baby and I don't have the racing thoughts. The only problem is that it is very difficult to get out of bed and move. " Zyprexa (olanzapina):9 "I have experienced significant cognitive problems as a side effect of olanzapine. Forgetting is pretty bad, and it can be alarming sometimes. When the dose was reduced, I saw the improvement, especially in my short-term memory. It is significant and remarkable. I'm leaving the medication just to address the memory problem, otherwise I would still take it for insomnia. Losing so much work memory makes it very difficult to read a lot, etc. " 5 "She realized, no matter how much mg of Olanzapina took in the day she would not only sleep. I'm taking 20 mg more than 24 hours. 10mg at night and 10mg in the afternoon but all I notice is that I don't sleep in the afternoon. " 5 Zyprexa (olanzapine): "After having tried almost all the medications. Zyprexa is the one who kept me asleep. Of course there are some mornings that I wake up early. Like 4-5 in the morning. Those nights are weird. As for weight gain? It wasn't a problem. And I wish everyone the best luck while taking these medications. Because finding the right fit requires a lot of patience:)" Zyprexa (olanzapina): 8 Zyprexa (olanzapine): "I went to a psychiatrist for sleeping medications and prescribed 5 mg. Zyprexa. It helped me sleep but as soon as I stopped taking medicine after two weeks, I experienced severe insomnia, sweating, palpitation, agitation depression and agitation. I had to get back on to stabilize. Now I'm taking 7.5 mg. I don't like the effect on me and I'll try to cut this medicine. I would like to know about the side effects and symptoms of the width of this medication. " Zyprexa (olanzapina):Next This information is NOT intended to support any particular medication. While these tests may be useful, they are not a substitute for the experience, knowledge and judgment of health professionals. Learn more about InsomniaIBM Watson MicromedexSymptoms and Treatments Drug.com Health Center Mayo Clinical Reference More about Olanzapina Consumer Resources Professional Resources Related Treatment Guides Drug Status Only required Rx CSA Table* It's not a controlled drug. N/A Loading... History of approval History of drugs in the FDA Loading..., , , , , , , , , , Mobile Apps The easiest way to find information about drugs, identify pills, check interactions and set up your own personal drug records. Available for Android and iOS devices. SupportAboutTerms " Privacy to Drug.com newsletters for latest drug news, new drug approvals, alerts and updates. Drug.com provides accurate and independent information about more than 24,000 prescription drugs, free-sale medicines and natural products. This material is provided only for educational purposes and is not intended for medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Data sources include IBM Watson Micromedex (updated 3 Mar 2021), Cerner MultumTM (updated 1 Mar 2021), ASHP (updated 3 Mar 2021) and others. Ad options

PDF) Olanzapine and clozapine differently affect sleep in patients with schizophrenia: Results from a double-blind, polysomnographic study and review of the literature

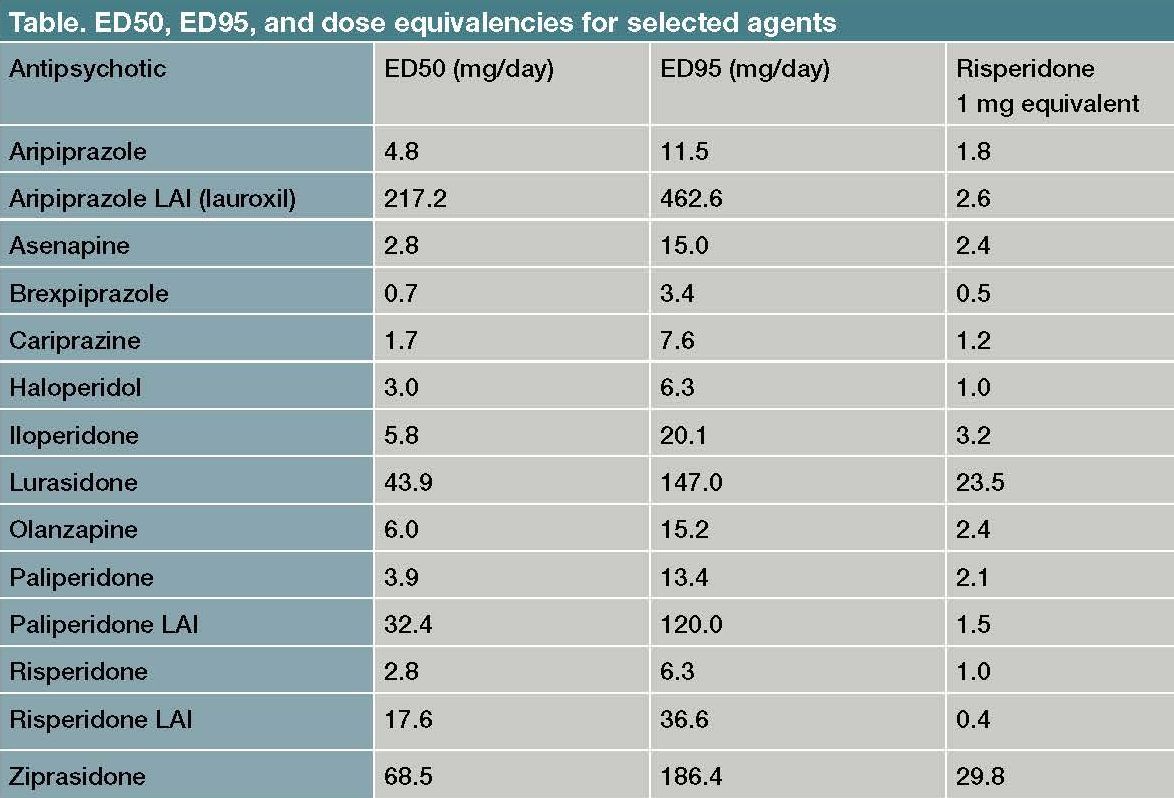

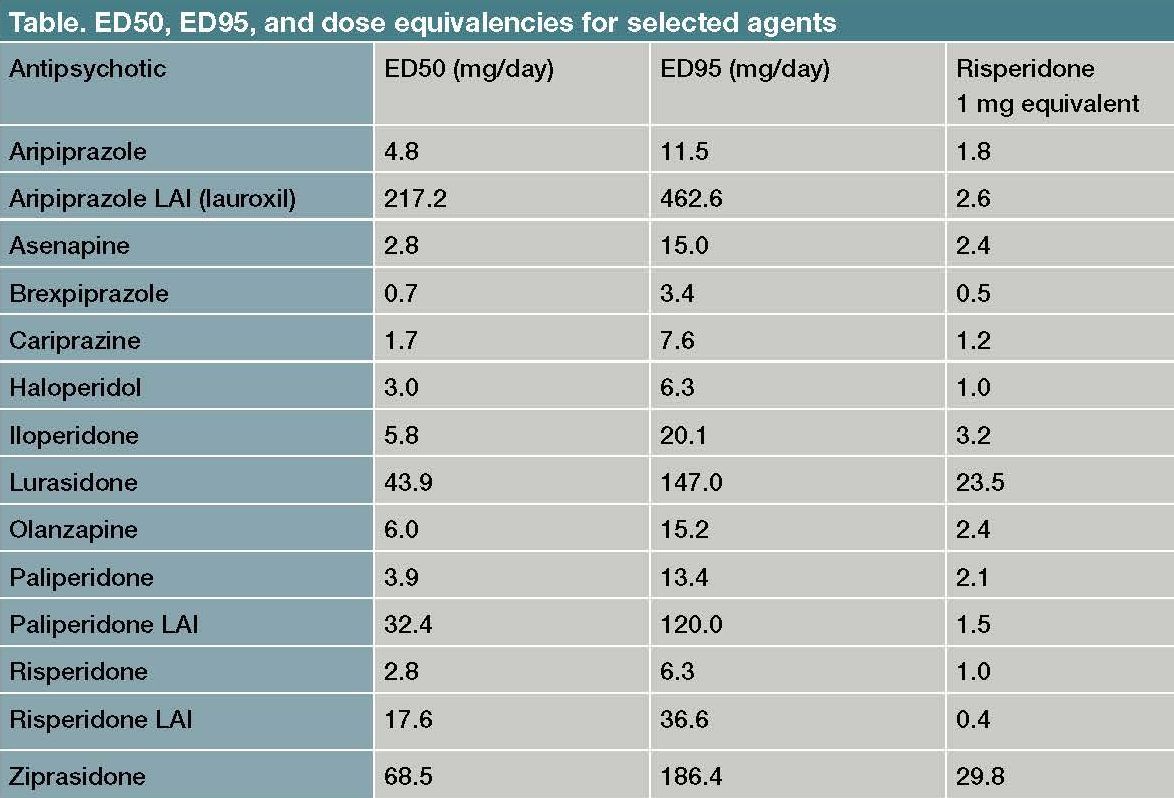

Antipsychotic Dosing in Acute Schizophrenia

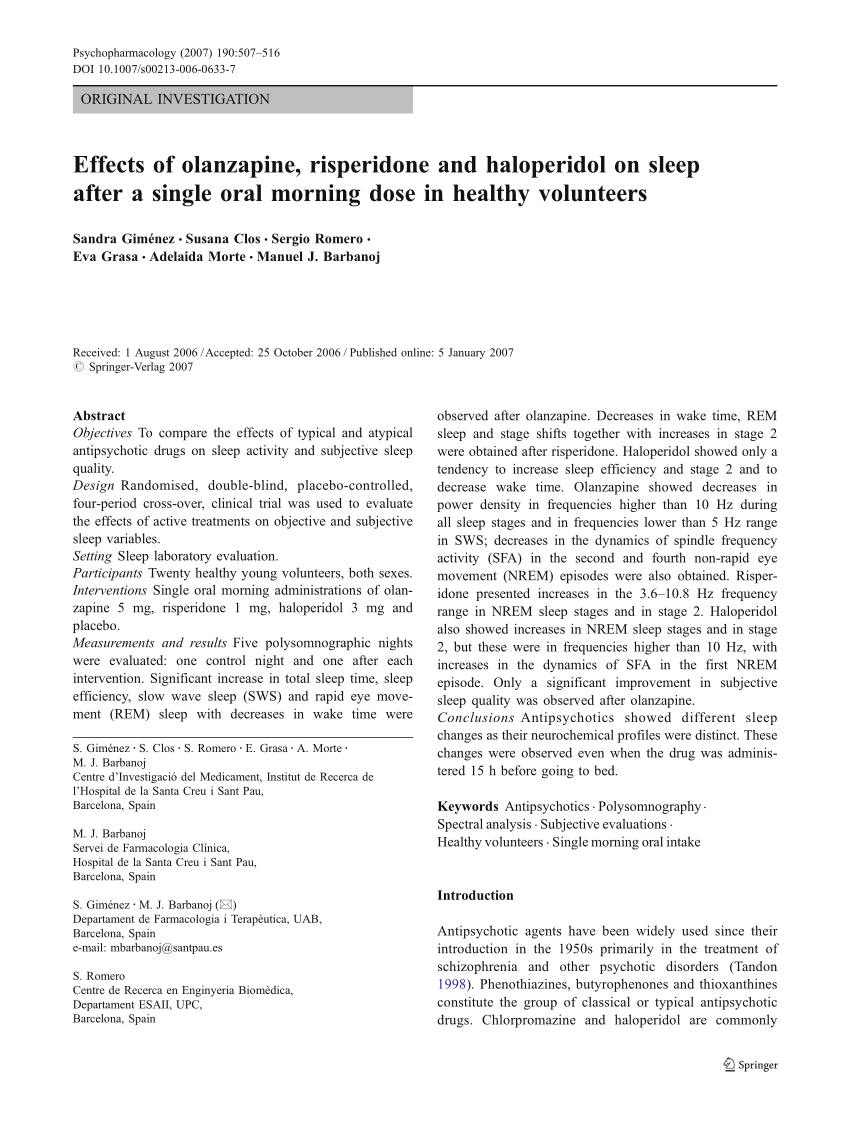

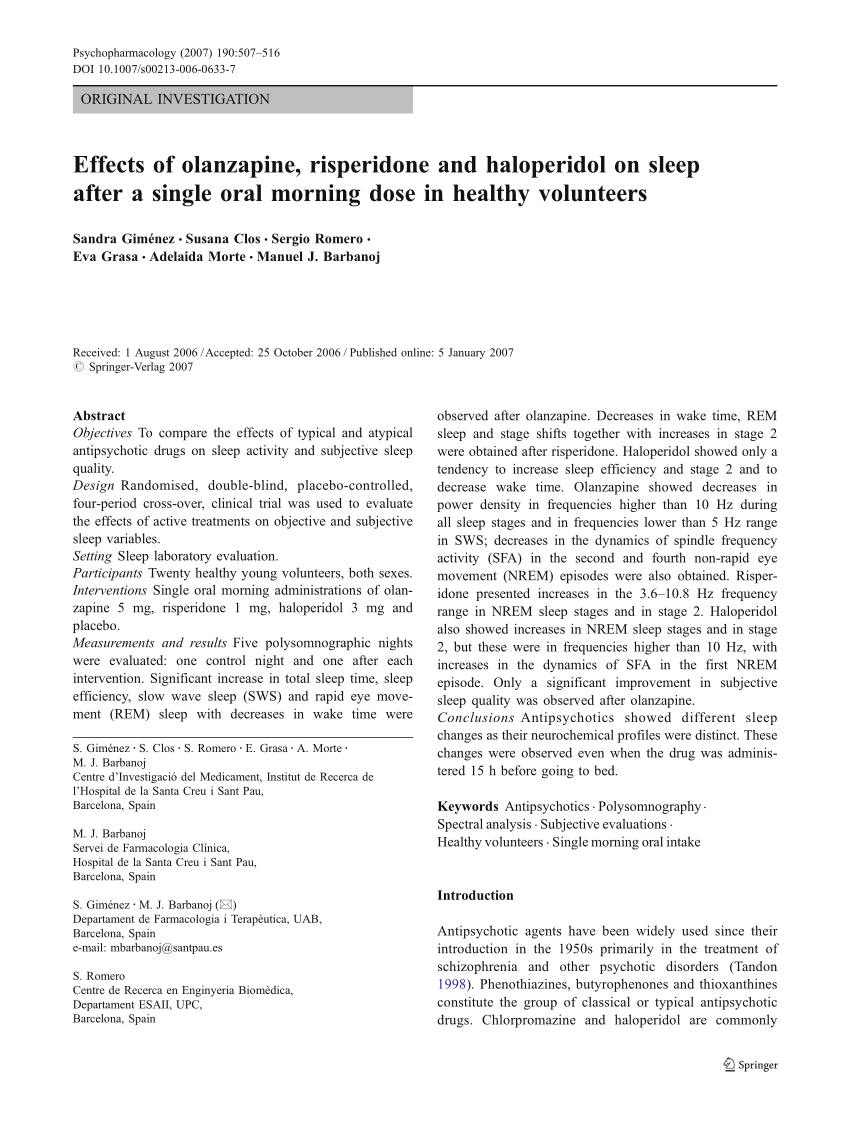

PDF) Effects of olanzapine, risperidone and haloperidol on sleep after a single oral morning dose in healthy volunteers

Delirium - EMCrit Project

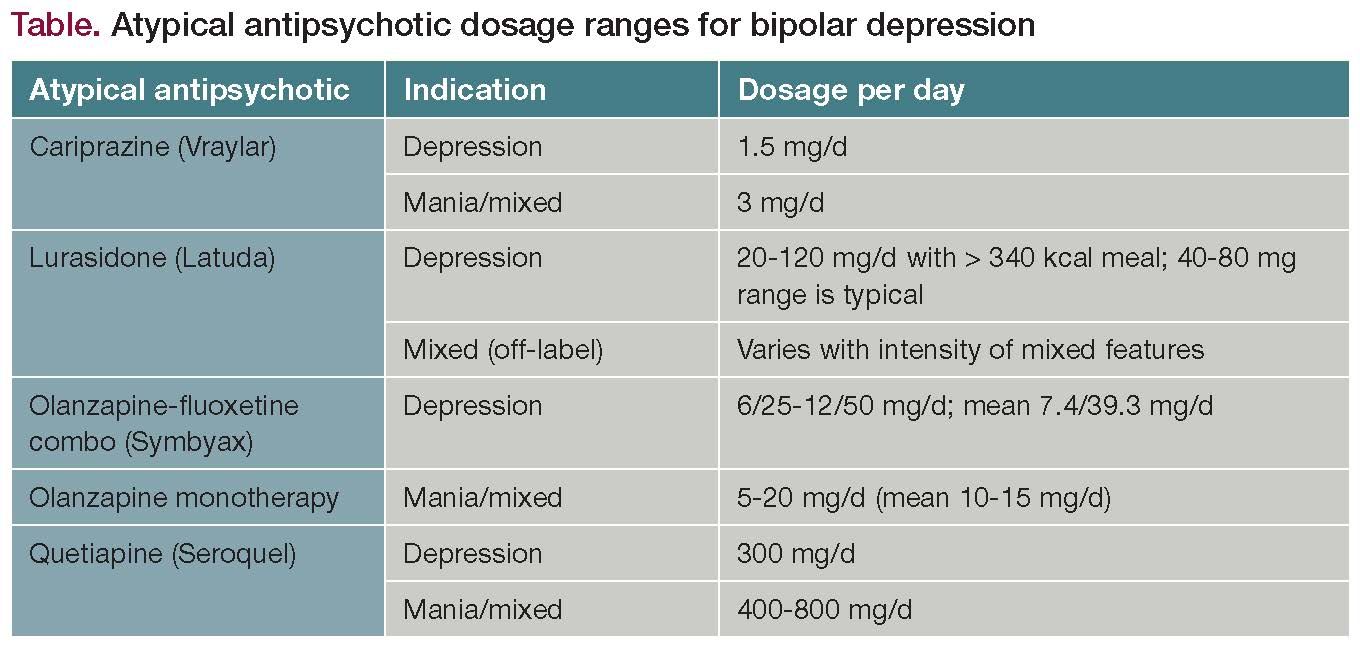

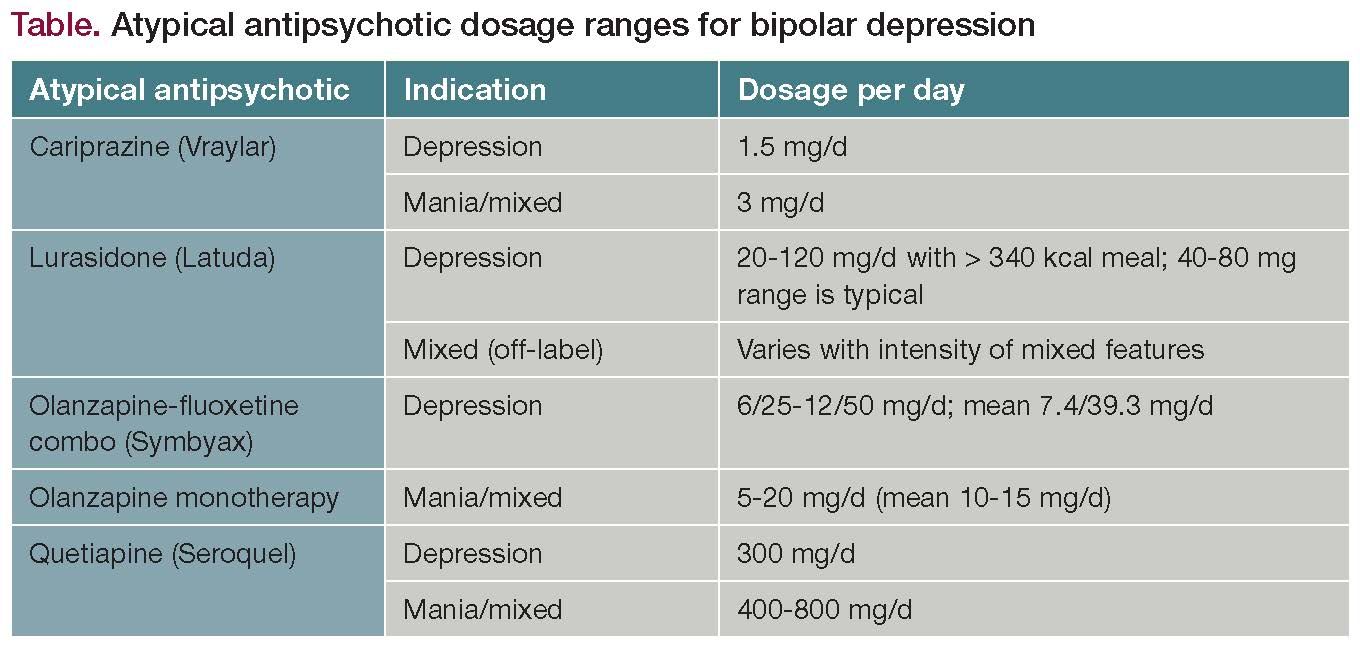

An Overview of Atypical Antipsychotics for Bipolar Depression

Etizolam - Uses, Side Effects, Interactions, Safety Measures & more | Medeaz

Atypical antipsychotics: sleep, sedation, and efficacy. | Semantic Scholar

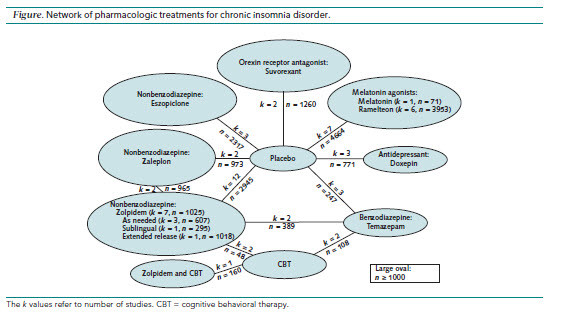

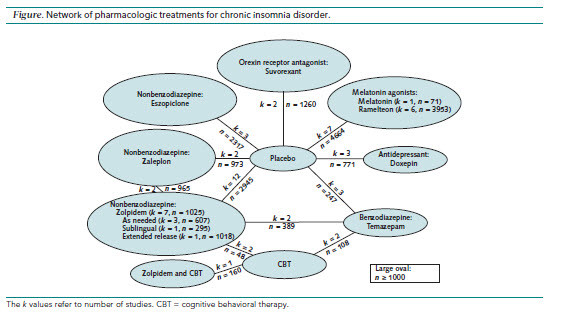

Insomnia: Pharmacologic Therapy - American Family Physician

Olanzapine Used For Sleep - ppt download

Olanzapine - Wikipedia

Trazodone for the treatment of sleep disorders in dementia: an open-label, observational and review study

Sleep architecture and cognitive changes in olanzapine-treated patients with depression: A double blind randomized placebo controlled trial | BMC Psychiatry | Full Text

PDF) Effects of olanzapine, risperidone and haloperidol on sleep after a single oral morning dose in healthy volunteers

Zyprexa Standard Dosage Buy Olanzapine Online olanzapine myopathy withdrawal from olanzapine and anxiety olanzapine d2 receptor occupancy olanzapine long. - ppt download

PulmCrit- Sedation update: IV olanzapine & combo vs. monotherapy

ZYPREXA Intramuscular | Healthgrades | (olanzapine tablet)

Olanzapine Withdrawal | RxISK

Can The The Pill Zyprexa Get You High Cheap Zyprexa Canadian Pharmacy zyprexa flakon olanzapine normal dosage zyprexa 10 mg cost uk the truth about zyprexa. - ppt download

Effect of Olanzapine on Clinical and Polysomnography Profiles in Patients with Schizophrenia

Children | Free Full-Text | Efficacy of Olanzapine for High and Moderate Emetogenic Chemotherapy in Children | HTML

PDF) Olanzapine and clozapine differently affect sleep in patients with schizophrenia: Results from a double-blind, polysomnographic study and review of the literature

Sleep Disorders & Dementia - Practical Neurology

Effect of Olanzapine on Clinical and Polysomnography Profiles in Patients with Schizophrenia

Sex differences in sleep after a single oral morning dose of olanzapine in healthy volunteers

Olanzapine 5 mg plus standard antiemetic therapy for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (J-FORCE): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial - The Lancet Oncology

Zyprexa Uspi olanzapine leukopenia zyprexa lilly 4112 olanzapine 2.5mg tab Only government bureaucrats would think it makes sense to keep a potential lifesaving. - ppt download

Olanzapine Fda Indications - PDF Free Download

Olanzapine (say: o-lans-a-pean)

Olanzapine - Wikipedia

FF #315 Olanzapine

Zyprexa Uses, Dosage & Side Effects - Drugs.com

Sleep architecture and cognitive changes in olanzapine-treated patients with depression: A double blind randomized placebo controlled trial | BMC Psychiatry | Full Text

Medications for Insomnia - Gateway Psychiatric

Case Report Olanzapine Dependence - German journal of psychiatry

Oleanz 2.5 MG Tablet - Uses, Dosage, Side Effects, Price, Composition | Practo

Olanzapine Reviews & Ratings at Drugs.com

Olanzapine-induced restless leg syndrome: A case report and review of literature | Semantic Scholar

APO-Olanzapine Film Coated Tablets - NPS MedicineWise

Olanzapine Help You Sleep

olanzapine pregnancy olanzapine overdose treatment olanzapine ketoacidosis olanzapine zopiclone olanzapine odt olanzapine chemical structure - PDF Free Download

Sleep architecture measures after one single oral morning... | Download Table

Sleep architecture measures after one single oral morning... | Download Table

Posting Komentar untuk "olanzapine dosage for sleep"